Film Review - The Girl with the Needle (2024)

- Alex Kelaru

- Mar 28

- 4 min read

Kelaru & Fulton rating: ★★★★★

Runtime: 2 hrs 3 mins

This is my vision of Hell.

A warning: this film will take you to the depths of sadness, grief, and despair like few others in recent memory. And yet, at the same time, it is a visually and emotionally stunning work of art.

If you’re ready for that, then…

Welcome to Copenhagen in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The city, drained of colour and life, is drowning in poverty and bureaucracy. Its people are mere shadows of themselves, they're hollowed out, surviving rather than living.

Karoline (Vic Carmen Sonne, Azrael, Miss Osaka), a widow, works a soulless job in a factory, cutting uniforms for soldiers still on the front lines. Her husband has been missing for over a year, and when we meet her, she is teetering on the edge of survival, about to be evicted from her modest home. The blow comes in the cruelest fashion: the landlord not only informs her that she must leave but also introduces the mother and daughter who will be moving in.

Less than ten minutes into the film, and we have already been immersed in its bleak, punishing world. Visually, it’s a masterclass in cinematography. The film’s black-and-white palette leans heavily toward shades of grey, with almost no pure white in sight. But now, we’re introduced to the brutal social structure of this time. Desperate to stay, Karoline tries to scare off the prospective tenants by telling the little girl the apartment is infested with rats. When the girl, frightened, tells her mother she doesn’t want to live there, her mother responds with a slap so hard it leaves the child with a nosebleed.

This moment is shocking, but also deeply telling. Here is a world where women are vessels for reproduction, stripped of autonomy, and locked in a relentless cycle of suffering. Hope is nowhere to be found.

Forced to move into a less salubrious flat, with a leaking ceiling and a bucket for a toilet, Karoline understands just how precarious her existence has become. The only glimpse of optimism comes from her work, where her tall, handsome manager Jorgen (Joachim Fjelstrup, Sult, Carmen Curlers) shows her kindness when she requests a widow’s benefit—something she is denied because her husband is missing, not officially dead. Their relationship begins as a lifeline for Karoline, something she sees as love and he enjoys as a distraction. She becomes pregnant, and they agree to marry.

But this is not a world where happiness lasts.

Jørgen’s domineering mother, who controls both the factory and her son’s life, forbids the marriage and fires Karoline. Pregnant, jobless, and trapped in a city that feels like a version of Dante’s Inferno, Karoline drifts through the haunted-grey streets, her hollow expression a perfect portrait of quiet despair.

And yet, this is only the beginning of her descent. There are still more circles of hell to pass through.

Determined to rid herself of the pregnancy, Karoline attempts to perform an abortion on herself in a public bath using a long needle. She is stopped by Dagmar (Trine Dyrholm, Poison, A Better World), a motherly figure who offers a solution: bring the baby to her after it is born and she will find a new, more caring home for the child.

Dagmar runs an illegal adoption business behind her candy shop, where she ‘helps’ women get rid of their unwanted babies. After Karoline gives birth to a girl, she visits Dagmar, and an unlikely bond forms between them, a bond that serves as the gateway to even deeper trauma, horror, and violence.

I won’t spoil what comes next, but the second half of this film is like staring into an abyss of human darkness. It forces you to witness what people are capable of, how far they can be pushed, and the horrors that emerge when survival comes at any cost. The world here is populated by wretches and witch-like figures, their eyes burning with a sinister vibrancy that makes them all the more terrifying.

As Karoline is pulled further into this nightmare, she slowly loses every last piece of herself. She becomes ghost-like, stripped of her soul, even denied the dignity of her own despair. When she finally attempts suicide, even that escape is taken from her. She is forced to strip away every motherly instinct, every last shred of humanity, until she is left with nothing but raw survival.

But this is not a film to be avoided because of its bleakness. Quite the opposite. This is a masterpiece, one that dissects what makes us human and then turns those findings against us. And it does so with haunting beauty.

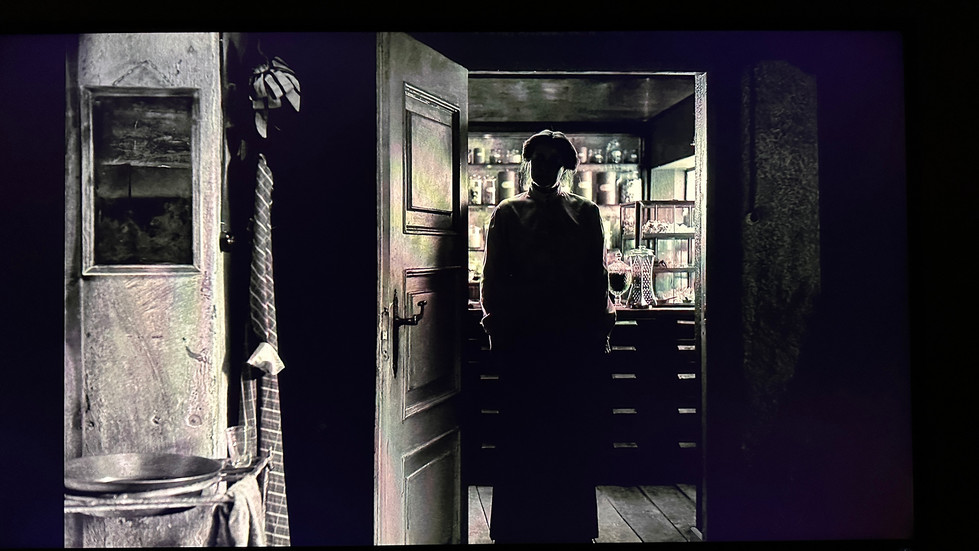

Visually, the film is a triumph. It echoes the look of German Expressionist cinema, every shot meticulously composed, every shadow deliberate. There were moments when I found myself pausing the film just to capture certain frames. They are that stunning. The music is equally unsettling, and the performances are extraordinary. Vic Carmen Sonne, as Karoline, conveys more with her face than most actors do with pages of dialogue. And Trine Dyrholm’s Dagmar? She secures her place in film history as one of the most terrifying villains of all time.

The world created by cinematographer Michal Dymek (A Real Pain, EO) is so tangible that you can feel the grime, the soot, the decay. Within the first ten minutes, you are so immersed in the Dickensian squalor that you almost want to look away.

While adoption and its dark history have been explored in cinema before, The Girl with the Needle is about more than that. It is about what humans do to themselves—the situations we create, the choices we are forced to make, and the ways in which suffering is perpetuated.

Mandatory viewing.

%20Logo%20Black%20over%20White.png)